Managing Injuries to Non-Independently Mobile Children – Practice Guidance

Introduction

It is recognised that the likelihood of a child sustaining accidental injuries increases with increased mobility. However, safeguarding children reviews have identified that professionals sometimes fail to recognise the highly predictive value, for child abuse, of the presence of injuries to non- independently mobile children.

Aim of this Guidance

The aim of this guidance is to provide all professionals working with children and families with a knowledge base and action strategy for the assessment and management of children who are not independently mobile and who present with injuries or bruising. Throughout this guidance injury is given to mean any bruise, mark, burn, scald, laceration, cut, abrasion suspected fracture, unexplained bleeding or any other apparent injury to a child

It is acknowledged that identifying possible abuse is particularly challenging and professional judgement and responsibility must be exercised at all times. However, in light of the evidence base this guidance remains necessarily directive as missed opportunities to identify physical abuse can be catastrophic. Any injury to a child who is not independently mobile should be treated as a matter of enquiry and concern.

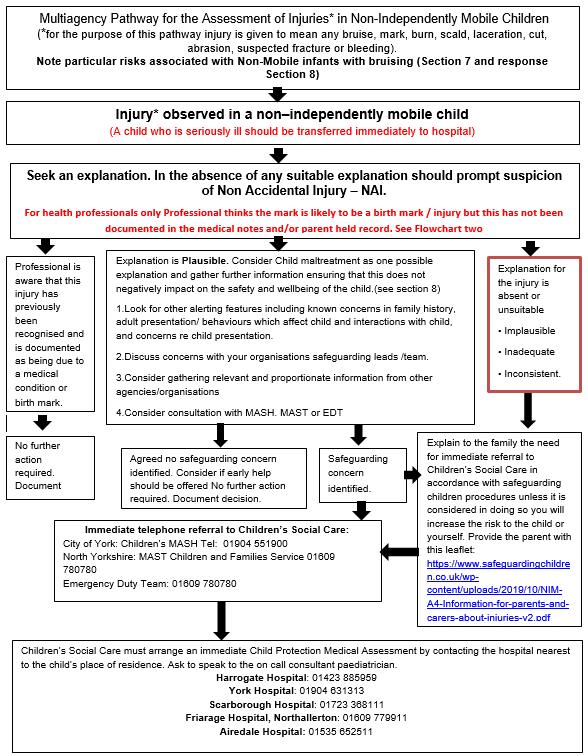

Please see following Flow Charts 1 and 2 as quick reference to actions required from all professionals. You should also review the narrative on pages 5 – 8 to gain further understanding of the research and critical nature of responding effectively to injuries in Non-Independently Mobile children.

Flow Chart One: Multi agency Pathway for the Assessment of Injuries in Non-Independently Mobile Children

Where required, professionals should seek advice / support from within their own organisations or via CSC. Multiagency Safeguarding Children Partnership Procedures should be followed at all times.

City of York: https://www.saferchildrenyork.org.uk/

North Yorkshire: http://www.safeguardingchildren.co.uk/

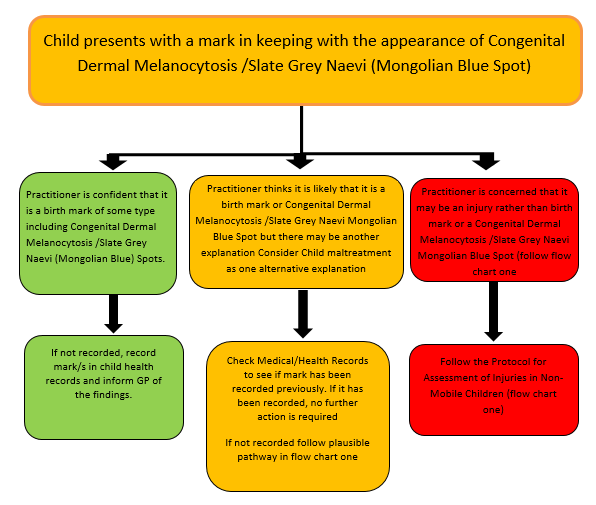

Flow Chart Two: Guidance for Health Professionals on Identification of Birth Marks including Congenital Dermal Melanocytosis /Slate Grey Naevi (Mongolian Blue Spots)

Examples of Congenital Dermal Melanocytosis/Slate Grey Naevi (Mongolian Blue Spot)

What are Congenital Dermal Melanocytosis /Slate Grey Naevi (Mongolian Blue Spots?)

- Hyper pigmented skin areas

- Usually seen at birth or early life

- Often familial

- Common in children of Asian/African descent

- Rarer in Caucasians

- Usually bluish/slate-grey in colour

- Usually flat & not raised, swollen or inflamed

- Usually round/ovoid but can be triangular, heart-shaped or linear

- Can be single or multiple marks

- Usually on the lower back/sacrum/buttocks

- Trunk, extremities (rarer)

- Face or scalp (extremely rare)

- Usually fade with age

Differentiation of Congenital Dermal Melanocytosis /Slate Grey Naevi

Mongolian Blue Spots from Bruising:

- Typical sites

- Non – tender

- Usually homogeneous in colour

- Don’t change colour and take months/years to disappear

- Must always document presence of Mongolian Spots, including how extensive, site and shape

Definitions and Terminology

Professionals: All individuals from all agencies working with children and families either directly or indirectly

Non-Independently Mobile: A child who is not yet walking, crawling, pulling to stand or bottom shuffling independently. This includes all children less than six months old as although some children can ‘roll over’ from a very early age this does not constitute self–mobility. The current evidence base concludes that accidental bruising is uncommon in a baby who is not independently mobile, particularly in those who are younger, unable to roll and unable to crawl. This guidance also includes children with physical disabilities who are not independently mobile.

Injuries: It is recognised that bruising is the most common presentation in children who have been physically abused (Maguire, 2010). However, for the purpose of this protocol, ‘injury’ will be taken to mean any bruise, mark, burn, scald, laceration, cut, abrasion suspected fracture, unexplained bleeding or any other apparent injury to a child.

Bruising with a medical explanation: Bruising in very young babies may be caused by medical issues such as birth trauma although this is very rare. This should always be documented in the child’s medical notes and parent held record.

Birth marks: Where practitioners are confident that a child has a birth mark of some type, including Congenital Dermal Melanocytosis /Slate Grey Naevi (Mongolian Blue Spot) this should be recorded in the child’s medical record and parent held record and GP informed

In cases where the practitioner thinks it is likely that it is a birth mark or Congenital Dermal Melanocytosis /Slate Grey Naevi (Mongolian Blue Spot) or other birth mark but is not sure and nothing is recorded in the child’s record, the practitioner should, if appropriate first seek advice from a senior colleague that same day. If uncertainty still remains after this second consultation or a second consultation is not feasible, the practitioner should seek advice from their own organisations safeguarding team the same day to discuss next actions required. The outcome and findings from these consultations should be documented in the child’s medical notes (Primary Care and/or hospital records) and Parent Held Record. (Flow chart 2)

Research Base

Very young children are the most vulnerable to the impact of physical abuse (Maguire, 2010). The Triennial Analysis of SCRs (Sidebotham et al, 2016) and four consecutive Biennial Analyses of Serious Case Reviews (Brandon et al, 2008; 2009; 2010; 2012) have identified that children under the age of 1 year are consistently over represented in Serious Case Reviews , almost exclusively because of severe injury or death as a result of physical abuse.

It is also recognised that all children with disabilities are at increased risk of abuse. Research suggests that children with disabilities are up to 3.4 times more likely to be abused or neglected than their non- disabled contemporaries (Sullivan and Knutson, 2000).

The Child Protection Evidence Systematic Review on Bruising (Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2020) concludes that ‘Bruising was the most common injury in children who have been abused. It is also a common injury in non-abused children, the exception to this being pre-mobile infants where accidental bruising is rare (0-1.3%). The number of bruises a child sustains through normal activity increases as they get older and their level of independent mobility increases.’

A review of the studies included in this systematic review suggest that accidental bruising is uncommon in pre-mobile infants, particularly in those who are younger, unable to roll and unable to crawl. However, accidental bruising in pre-mobile infants is not unknown, with the numbers found to have a bruise on a single observation ranging from 0.6-5.3% in those who were not yet rolling or crawling. Accidental bruising is more common in more mobile children, in one study being found in up to 17.3% of those who were crawling but not yet cruising, and 17.8% in those who were crawling and cruising but not yet walking.

Responding to injuries to immobile children/ infants

When an immobile child presents to a professional with injuries the possibility of maltreatment must always be considered/ suspected as per NICE guidance ‘When to suspect Child Maltreatment’ which provides a summary of the presenting features associated with abuse.

Key aspects of the assessment must also include seeking an explanation for the injury from the parent or carer and an understanding regarding the child’s developmental stage. It is also essential to consider any other issues which would raise your concerns.

- If you require further advice or guidance you must speak to the person within your organisation who is responsible for offering safeguarding advice, the same working day. If they are unavailable you must discuss your concerns with Children’s Social Care (CSC).

Note: It is important to recognise that bruising in an immobile infant presents particular safeguarding risks as highlighted in the systematic review by the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel (2022). The professional response must be to speak with their organisational safeguarding lead and consideration should include a multi-agency discussion (not necessarily a strategy meeting) with the MAST/ MASH. Consideration should always be given for a child protection medical assessment: the expectation being that such an assessment will take place.

Referring your concerns to Children’s Social Care

Where a decision to make a referral to CSC is made it is the responsibility of the professional who first learns of or observes the injury to make the referral following Local Safeguarding Children Partnership Procedures. It is important that the individual who noticed the injury speaks with their safeguarding lead in respect of the concerns and explores the questions set in the section above Pg 8. The question set above should assist in deciding if a referral to children’s social care is required. If a referral is needed, this must be completed on the same day as the injury being noted.

City of York MASH and North Yorkshire MAST screen the referral using expertise from Multi Agency partners; Children’s Social Care, Health and Police. Health representation will take the lead in reviewing information, obtaining information from the individual who reviewed the child and share this information within the multi-agency discussion. The MASH/ MAST discussion is a multi-agency discussion and will consider any other information on the child and family and any known risks, and to jointly decide whether any further assessment, investigation or action is needed to support the family or protect the child.

An action from this discussion could be a strategy meeting which is where it is decided if a Child Protection Medical Assessment (CPMA) should be undertaken.

The referral should be made the same working day. A Child Protection Medical Assessment CPMA and relevant investigations must be undertaken by the on-call Paediatrician. CSC are responsible for arranging this CPMA. A Social Worker should also attend the assessment wherever possible. The CPMA should take place within the same day/ or within 24 hrs. Timing of examinations is critical to ensure any underlying injuries are identified and treated. It is also important to secure any forensic evidence.

The professional making the referral and the Social Worker receiving the referral must reach a decision as to whether the child can be safely transported to the hospital by the parent or carer alone or whether the child should be accompanied to the hospital by a CSC professional. If the decision is that the child needs to be accompanied to the hospital, then the professional making the referral and the Social Worker should agree if it is necessary for the professional to stay with the child until CSC are able to attend to accompany the child to the assessment.

Should any professional be dissatisfied with another agency/professional’s response to their concern or proposed plan of action they should seek advice from the professional within their organisations who is responsible for offering safeguarding advice and/or access their Safeguarding Children Partnerships professional resolution/escalation procedures.

NB: Any child who is found to need urgent medical treatment, and in whom abuse is suspected, should be transferred immediately, by ambulance, to the nearest hospital Emergency Department (ED). The professional with the concern must have a direct conversation with the senior manager in ED (Nurse in Charge or Consultant) explaining the nature of the concern, with particular reference to the safeguarding issues. The professional with the concern must also make an urgent referral to CSC.

If a parent is uncooperative and refuses to take the child for a CPMA, or fails to attend the assessment as agreed, this should be reported immediately to CSC and if the child is thought to be at immediate risk of harm the police must be contacted by dialling 999.

Keeping parents informed

Parents or carers must be kept informed as far as possible throughout this process providing this does not present a risk to the child or the professional. An information leaflet will support you in explaining to parents why the referral to CSC and the CPMA.

Parent and Carer leaflet:

Documentation

The importance of accurate, comprehensive, and contemporaneous documentation cannot be overemphasised. In cases of possible non accidental injury the explanation for the injury can change over time. Your documentation can be crucial in supporting professionals to protect the child from further harm. Your documentation may also be used in a subsequent criminal investigation or other court processes.

Key contacts

City of York Multi Agency Safeguarding Hub (MASH) 01904 551900

North Yorkshire Multi Agency Screening Team (MAST): 0300 131 2 131

Emergency Duty Team: 0300 131 2 131

Safeguarding Children Partnerships Procedures

City of York: www.saferchildrenyork.org.uk

North Yorkshire: www.safeguardingchildren.co.uk

References

Brandon et al (2008) Analysing Child Deaths and Serious Injury through abuse and neglect: what can we learn? A Biennale Analysis of Serious Case Reviews 2003-2005. London. . Department for Children, Schools and Families.

Brandon et al (2009) Understanding Serious Case Reviews and their Impact: A biennial analysis of Serious Case Reviews: 2005-2007.London. Department for Children, Schools and Families.

Brandon et al (2012). New Learning from Serious Case Reviews: A Two Year Report for 2009-2011. London. Department for Education.

Brandon et al (2010). Building on the Learning from Serious Case Reviews: a two year analysis of child protection database notifications 2007-2009.London. Department for Education.

Maguire, S. (2010). Which injuries may indicate child abuse? Archives of Disease in Childhood: Education and Practice Edition, 95(6), 170-177. doi:10.1136/adc.2009.170431

Sullivan, P.M. & Knutson, J.F. (2000). Maltreatment and Disabilities: A population based epidemiological study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24 (10), 1257-1273

Sidebotham et al (2016) Pathways to harm, pathways to protection: A Triennial Analysis of Serious Case Reviews 2011-2014. London. Department for Education

The Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel (2022) Bruising in non-mobile infants Panel Briefing 1 September 2022

Last Updated: 12 June 2023

View all our news

View all our news